I’ve been painting a contemporary landscape in my head for a long time. The idea first appeared about five years ago while working on the tiny plot of organic vegetables at the back my house. I was just putting in my rocket salads when along came this guy with a giant mechanical machine spraying chemicals on the field surrounding us. Until recently this had been a meadow with a very diverse ecosystem. I liked the wildness of it, and it often made me think of the English painter Constable and his clear recording of his landscapes of 1800s England.

I began to look at his paintings in books and went to see some originals in the National Gallery in London. I spoke to an art historian who specialises in 1800’s Irish and English art. In his view, Constable was "sentimentalised by being put on chocolate boxes and that he was a very powerful painter of the environment of his day”. Slowly a thought began to form; what is the environment of my day?

Soon after I started drawing images of what I imagined to be futuristic Mechanical Pollen. Initially on phone bills and the back of notes but quickly I filled sketchbooks with the things. In my mind's eye, I saw them propelling all around our house at different nanosecond speeds. Sometimes they looked like a snitch from a Quidditch game, other times more like flying pollen with many tiny propellers. I began to look at books on pollen, and I have to say it’s crazy what is out there, nature is a master of functional art. Ideas came flooding in, and I played around with the idea of making sculptures in aluminium or bronze, but it stayed in the drawing stage.

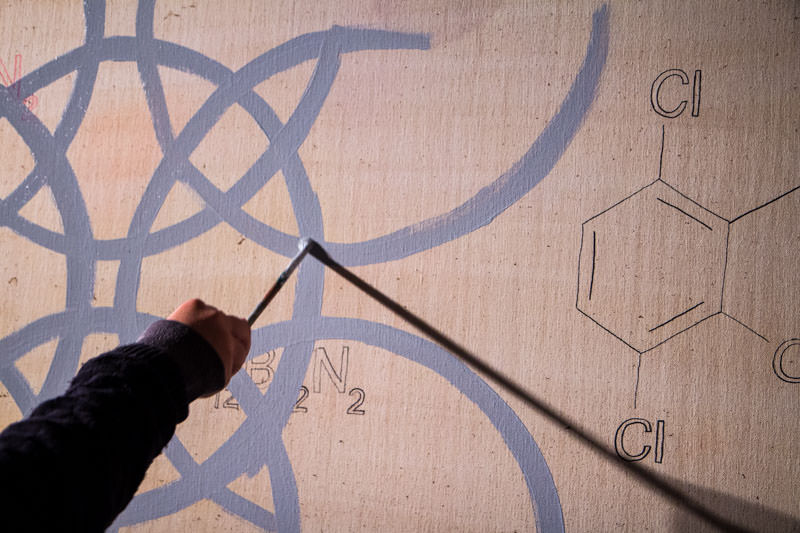

I read up on contemporary farming, and some of the chemicals invented to assist the modern growing techniques. I had no real idea why, but I was drawn to the shapes of the chemical formulae of weedkillers and fertilisers. The compounds looked almost sculptural. Their trade names were like characters in an X-Men movie.

What has any of this got to do with an interpretation of a landscape? I wasn’t sure myself, but gradually I formed a concept of a series of paintings exploring a contemporary landscape. I felt that they needed to have a sense of beauty and energy, but also a newer truth of their mechanical makeup.

Most ideas stay in the drawing stage for years, some never reappear. The expansion of the Chemical Constables concept was derailed by the forceful chance encounter I had with Paulo Uccello's battle scene in the National Gallery London. It was such a profound experience and changed forever how I abstract shapes and colours in my surroundings. I went on to travel to Italy several times over the years to study Renaissance art.

In the spring of 2017, as I was preparing to return to Italy to paint for the summer, I got a delivery of these two large linen canvases I had made to the size I thought my contemporary landscapes should be.

I spent the summer looking at Masaccio’s frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel Florence and Piero della Francesca's work in Arezzo. I came away from these masterpieces with an unusual imprint of sorts. Their scale is monumental, the height they are placed at just adds to that. I found myself focusing on the feet of St. Peter and those surrounding him. In the case of the Piero Della Francesca frescoes, I was drawn to the legs of the horses. Back in my studio, these feet began to change into distinct abstract shapes. I tried them on smaller canvases, but I couldn’t get them to work in the way I needed. I kept painting over them.

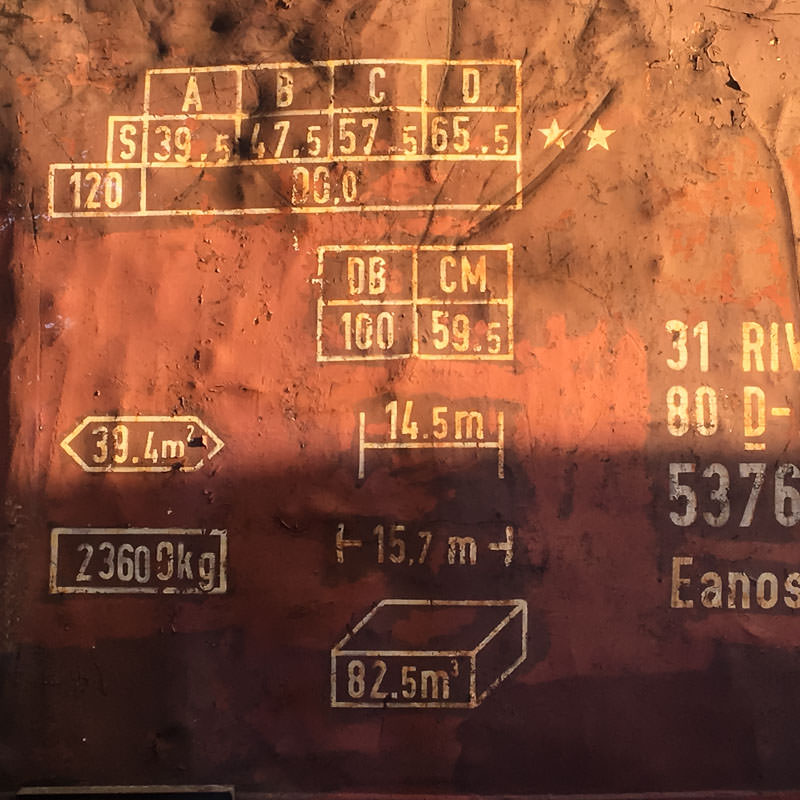

Throughout the summer I went on many train journeys to chase art from Florence to Munich. I don’t get to see many trains in Ireland, so I was mesmerised by the sunlit industrial aesthetic of the freight trains. The flakey dryness of their sun-bleached, rusted metal bodies and especially the stencilled, technical hieroglyphs on the side of each carriage. The typography and the industrial sense surrounding it conjured up images of the abstract chemical compounds I had drawn years before. I decided that I needed to incorporate that aesthetic into the landscape paintings.

A conversation about the repeating structure of fractal patterns in nature around the same time offered a further strand that became woven into those pieces. I had recently bought a book on Japanese Katagami patterns which I was jonesing to use somewhere in my work. The idea of repeating patterns and the layout of chemical compounds began formulating in my head. I know all this seems very random, but it’s how I work. Chance encounters, lazy cul-de-sac investigations, inspiring moments, all simmer on the sidelines waiting to manifest as new work.

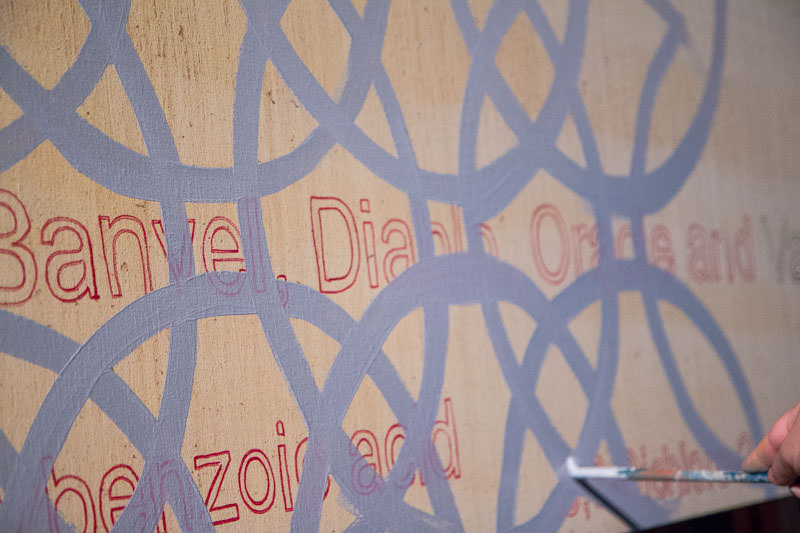

These two canvases were built up in parallel. I created an old-fashioned acetate of the chemical formulae and compound names, their spacing guided by the overall look of the lettering on the train carriages. I projected them onto the oil-washed canvases with this ancient overhead projector I fished out of a skip some twenty years ago. I kept it through many studio moves, never using it until that moment. A second acetate allowed me to trace the Katagami pattern with greyish oil paint. I’ve never worked like this before, even the fact that I had to wait till nightfall for it to be dark enough to use the projector was an unusual but oddly exciting restriction.

I knew from the outset that I would have to paint over it, but I still spent days looking at it before covering it with a tinted oil wash. I watched the canvases dry for days, intrigued and uplifted by these two new species in my usual habitat. Then I grabbed a brush and went for it, painting purely on instinct. After years of assimilation, I discarded all the built-up cognitive direction and felt my way through the work.

Scale matters. Working on large canvases is different, there is almost a theatrical element to it. They give a sensation of stepping into the work. As a viewer, I am enveloped by their scale and can feel part of the whole. The lines between subject, object and activity become blurred.

Over the course of the following months, as I was increasingly sinking into the pieces, the Italian forms appeared. I needed the blocky sculptural shapes as a ballast to keep the work from flying away. The more I painted, the more of the Katagami print sections and chemical text I lost. There is a constant battle between what you want to keep and what you want to add. Like a writer, you have to kill your darlings for the integrity of the work.

There were so many different themes flowing into these pieces that I began to think of them as a musical performance. At this point of peak activity, the hardest thing to do is to create pauses in the work, areas of inactive space that help you to navigate the final piece.

Watching paint dry, contrary to general belief, can be fun. I use this time to find titles that might help the viewer to enter into the work. I gather up the linguistic snippets that swarm around the pieces for the period that they are in my studio. Words are powerful things, but I sometimes don’t register their use or meaning in the context that they were intended. I shape titles out of context. I think by redirecting words that way a title can point a viewer to the essences of a painting in a more compelling way than a direct finger could.